BREAKFAST BIBLE STUDY

Judah Liked Sex Workers at Shrines

Genesis 38: 12-26 (NIV)

9/21/25

“Christian nationalism is about power, nothing more.” – Christian Pecker

I pretty much know the story of Judah and Tamar because I was worried about blood curses when I thought I made Jesse pregnant, but parts of the story still do not make sense to me, and parts of the story are probably not appropriate for school children. Those parts of the story always made sense to me, but I hoped Grace and Christian could explain everything else. Since Christian and I have been getting ready to harvest, he slept in late this morning to rest his back, but Grace brought out fruit salad from last night to have with our oatmeal.

“Judah slept with Tamar on accident,” I said. “She tricked him.”

“So…it was okay for him to have sex with her?” Grace asked.

“She tricked him,” I said. “She was in disguise.”

“As what?” Grace said.

“Something bad. I better read it again,” I said. “This is from Genesis 38. ‘Judah then said to his daughter-in-law Tamar, “Live as a widow in your father’s household until my son Shelah grows up.” For he thought, “He may die too, just like his brothers.” So Tamar went to live in her father’s household.’ See, that part was good because he was going to let her have his youngest son as a husband, but she had to wait until he was old enough.”

“The ‘he may die too’ part implies that Judah had no intention of arranging a marriage between Shelah and Tamar,” Grace said.

“‘After a long time Judah’s wife, the daughter of Shua, died. When Judah had recovered from his grief, he went up to Timnah, to the men who were shearing his sheep, and his friend Hirah the Adullamite went with him.’ Wait, what’s an Adullamite?”

“Ask Christian,” Grace said.

“Ask me what?” Christian yawned as he came into the kitchen.

“What’s an Adullamite?”

“A person from Adullum in Judah,” Christian said. “A lot of these cities in Judah were established before the Bronze Age collapse. The Philistine, Canaanite, and Israelite peoples were those in the region left after that collapse. They vied for power in the territory when the Hittites and Egyptians withdrew.”

“What’s that have to do with Judah and Tamar?” I asked.

“Nothing, I guess,” Christian said. “Judah and Tamar, if they existed, would have lived before the Bronze Age collapse. I guess this gives us some location context.”

Since I had no idea what Christian meant, I kept reading: “‘When Tamar was told, “Your father-in-law is on his way to Timnah to shear his sheep,” she took off her widow’s clothes, covered herself with a veil to disguise herself, and then sat down at the entrance to Enaim, which is on the road to Timnah. For she saw that, though Shelah had now grown up, she had not been given to him as his wife.’ Oh, wait, so Judah didn’t let Shelah marry Tamar?”

“He probably feared Shelah might die as well,” Christian said, “as if Tamar might have been the cause of some familial curse.”

“I thought God killed them because they were wicked,” I said.

“Sure,” Christian said. “Or maybe Tamar carried some sort of pathogen.”

“Yes, blame the woman,” Grace said.

“I’m just speculating,” Christian said. “People from one tribe could be immune to diseases that affect other tribes. But the text does say that God killed them.”

“So…by that logic, prostitution isn’t wicked in this folktale?” Grace said.

Since I do not like when Grace and Christian argue, I interrupt by reading: “‘When Judah saw her, he thought she was a prostitute, for she had covered her face. Not realizing that she was his daughter-in-law, he went over to her by the roadside and said, “Come now, let me sleep with you.”’”

“Hmm,” Grace said. “What was her disguise?”

“Prostitute,” I said. “That’s a sin.”

“And who was soliciting the prostitution?” Grace asked.

“Judah, I guess.”

“They bartered and traded,” Christian said. “He offered her a goat.”

“What’s the pledge part mean? Is it like the Pledge of Allegiance?” I asked.

“He wasn’t carrying a goat in his pocket,” Christian said. “He had to offer collateral.”

“She was clever,” Grace said. “She took a pledge offering that was identifiable to Judah. If his personal belongings were a means of trade, Tamar would have proof that Judah owed her something tangible for some service rendered.”

“His cloak and stuff,” I said. “I remember that part…and then it gets dirty.”

“So, she was trying to get pregnant by her father-in-law?” Grace said.

“I think that’s what it means,” I said.

“And that was her only value,” Grace said. “Sex and breeding. Swell story.”

“Wouldn’t her child get Judah’s inheritance?” I asked.

“If she had a boy,” Grace said.

“Maybe Judah should have married an Israelite,” I said. “God would have liked that. I don’t think Tamar was an Israelite.”

“Judah would have had to marry a daughter or niece to accomplish that feat,” Christian said.

“Huh?”

“Judah was Jacob’s son,” Christian said. “Jacob was Israel. Judah, according to the Bible, was the father of the southern kingdom of Judah. The only Israelites at the time Judah was alive would have been the offspring of Jacob—Judah’s close family relatives. There were no Israelites, except in Judah’s immediate family. Get it now?”

“Oh, so Jacob’s sons were like the first twelve tribes?” I asked.

“Yes,” Grace said, “which meant there were no Israelites to marry without inbreeding.”

“Judah married a Canaanite,” I said. “They came from Canaan, Noah’s son. He was cursed. We’re doing that one next week.”

“Many scholars and archaeologists believe that the difference between Canaanites and Israelites was geographical,” Christian said. “Israelites were rural people. Canaanites were city dwellers. Farmers versus Herders. That said, the word Israel predates biblical accounts by hundreds of years. It appears in much older inscriptions in other regional cultures.”

“We’re rural people,” I said, “just like the Israelites. But we’re farmers, too. Just like Canaanites. Wait…the story means that Judah had to marry outside his tribe, right?”

“Correct,” Christian said.

“Tamar is part of Jesus’ bloodline,” I said. “And so is Judah.”

“The family line has a bit of a kink there, wouldn’t you say?” Grace asked.

“But they weren’t blood relatives,” I said. “I know that part.”

“So, should fathers-in-law be sleeping with daughters-in-law?” Grace asked.

“I think that’s probably against the law nowadays,” I said. “I think it’s probably against Moses, too, but he wasn’t even born back then, so Tamar probably didn’t know it was wrong to pretend to be a prostitute to trick her father-in-law.”

“Oh, really? The story isn’t finished,” Grace said. “Keep reading, Cole.”

“‘Meanwhile Judah sent the young goat by his friend the Adullamite in order to get his pledge back from the woman, but he did not find her. He asked the men who lived there, “Where is the shrine prostitute who was beside the road at Enaim?’”

“So, wait,” Christian said. “Back up. Was prostitution wrong?”

“Oh, yes,” I said.

“But Judah’s asking around about a prostitute?” Grace said.

“Maybe it wasn’t so wrong?” I asked. “Wait, what’s a shrine prostitute?”

“Remember Asherah worship?” Christian asked.

“They got rid of that,” I said. “God didn’t like it.”

“I would argue that forbidding Asherah worship was about consolidating power,” Christian said, “but associated with female goddesses may have been prostitution. I believe we have no direct evidence, but this story might imply something was going on at a shrine involving prostitution…unless this story is just a dig at those who did worship Asherah.”

“God must not have liked any of that,” I said. “Prostitution and idolatry.”

“Sure,” Christian said, “but women in these days might have been given to these cults as slaves. They might not have had much of a choice. Women had few options in the ancient world. If these women did have a choice, they still needed to eat.”

“That’s why she wanted a goat?” I asked.

“It’s food,” Grace said. “Keep reading. Summarize if you like.”

“The people tell Judah that there aren’t shrine prostitutes here,” I said. “So, Judah goes home and decides to let the prostitute keep his collateral so that nobody laughs at him. Three months later, Tamar is pregnant. They think she’s a prostitute. Judah says to burn her to death.”

“Hold up there,” Grace said. “Why does he want her burnt to death?”

“Because of the law?” I asked.

“What law?” Grace said. “Moses hadn’t written the law.”

“He probably knew it was a pretty bad sin, and this was before Jesus,” I said.

“So, it’s okay for him to solicit sex work,” Grace said, “but not okay for her—?”

“I get it now! He’s a hypocrite,” I said. “He doesn’t want to be a laughingstock for his sin. For her sin, he wants her burned to death.”

“Hypocrite. Good word choice,” Christian said.

“And why would they assume that she was guilty of prostitution?” Grace said.

“Because she was pregnant?” I asked.

“Maybe she was raped,” Grace said. “But nobody gives her the benefit of the doubt.”

“That’s not what the text says,” I said.

“That’s because the story itself is immoral,” Grace said.

I kept reading: “‘As she was being brought out, she sent a message to her father-in-law. “I am pregnant by the man who owns these,” she said. And she added, “See if you recognize whose seal and cord and staff these are.”

“She set him up,” Christian said.

I kept reading: “‘Judah recognized them and said, “She is more righteous than I, since I wouldn’t give her to my son Shelah.” And he did not sleep with her again.’”

“She goes from cursed to righteous?” Grace said.

“Judah’s not a very good person, is he?” I asked.

“He’s a product of his time and the culture,” Christian said.

“Which makes none of it right,” Grace said.

“Was she righteous because Judah knew that they would be ancestors of Jesus?” I asked.

“That’s how Christians might interpret the text,” Christian said.

“But is that what he thought?” I asked.

“Is that what the text says?” Christian asked. “Is there any mention of Jesus in this story?”

“I guess not.”

“She gave Judah a son biologically,” Grace said, “and, perhaps, a son legally. She secured an inheritance and made sure Judah’s bloodline persisted. I think that’s the point.”

“That’s what I thought I was with Grandpa and Mom,” I said.

“Which we know is not true,” Grace said.

“I know,” I said. “We have the DNA. I’m not Grandpa’s son.”

“So, what’s the moral lesson of this story that might be good for children to hear?” Grace said. “These clearly were important people, said to be ancestors of Jesus.”

“Good can come from sin?” I asked.

“And that’s what you want to teach children?” Grace said.

“I wouldn’t teach this story at all,” I said. “It has bad stuff all over it, so do a lot of these stories. None of it is appropriate for kids. And I bet if Christian nationalists would know about these stories, they would probably have a fit.”

“Christian nationalism is about power,” Christian said, “nothing more.”

In state legislatures across the country, Christian fundamentalists are passing laws meant to force the teaching of the Christian Bible in public schools. From the posting of textually inaccurate iterations of the Ten Commandments on the walls of classrooms to the incorporation of the “Trump Bible” across multiple pedagogical disciplines, these laws and mandates are sweeping the reddest parts of this nation.

The height of hypocrisy is banning books in the name of “protecting children” while mandating one particular book rife with numerous acts of sexual violence and scenes of graphic violence and genocide.

Book bans are dangerous. The Bible is worth reading and exists online and in public school libraries across the country, but proponents of mandating its formal teaching in public schools need to know what it actually says.

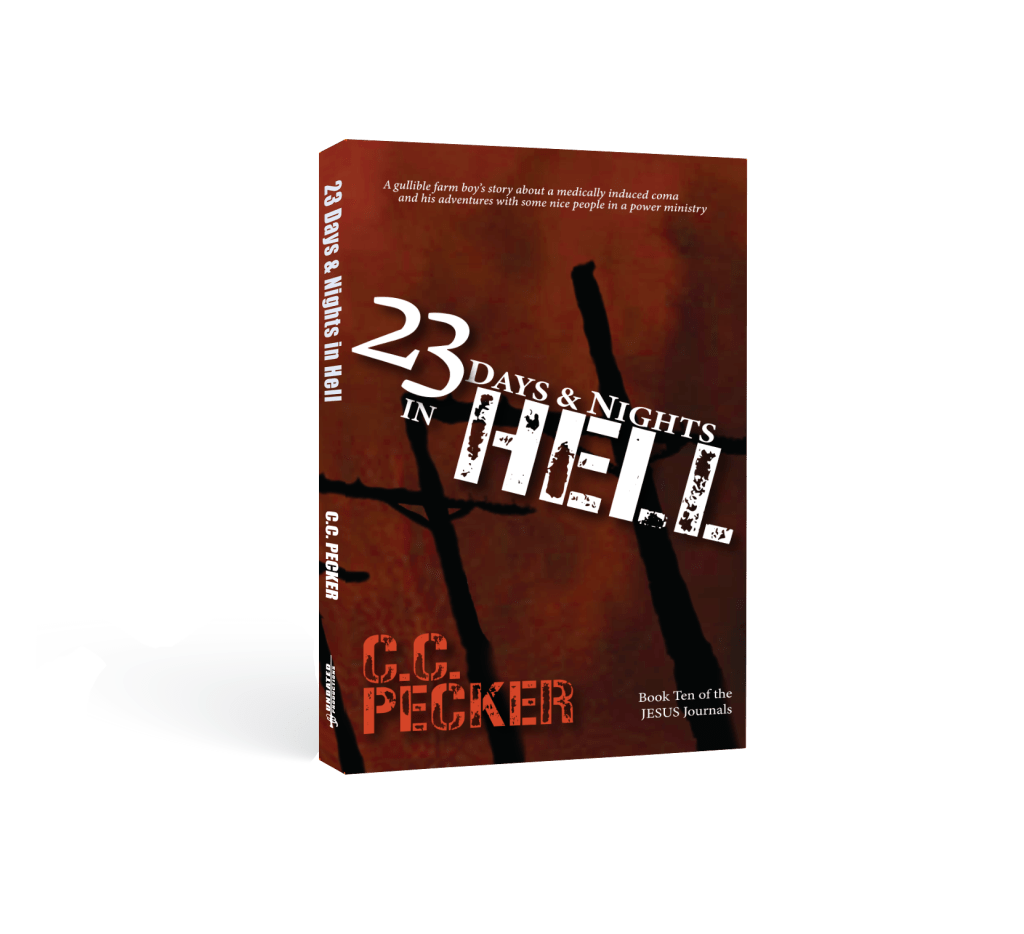

Some themes in my books below might not be appropriate for children.

© Copyright UNBATED Productions 2025