BREAKFAST BIBLE STUDY

When Israel was a Child

Hosea 11:1 (NIV)

2/15/26

“When Israel was a child, I loved him, and out of Egypt I called my son.”

– Hosea

February is my least favorite month because most of the time we need to stay inside and cannot get much work done, except in the barn… only this year, it’s been unseasonably warm, with little moisture. But that doesn’t change the fact that we still have work in the barn.

The only thing I like about February this year is that it reminds me of Natti, and I can spend the nights looking for Bible passages that prophesy about Jesus.

This week, I came across a prophecy that predicts what happens when Jesus was a little boy and had to run to Egypt. When I show it to Christian and Grace, they exchange looks that tell me I might have beaten them this time.

“Hosea says that Jesus will be called out of Egypt, which is exactly what happens in the Christmas story,” I said. “His parents take him there to keep him from the slaughter of the innocents in Bethlehem. Hosea predicted Jesus way before Jesus was born.”

“Fair enough,” Christian said.

“I proved it?”

“We don’t want to ruin the Christmas story for you,” Grace said.

“It’s not about Christmas. It’s about immigration,” I said. “See, Egypt must have been better than the United States is right now. They let people flee there from Israel without Egyptian ICE being evil and arresting refugees who are following all the rules to become citizens, even people who were little kids when they came here, just like Jesus, and have been working hard and making America better. See, it’s about ICE and Trump being as evil as Herod and the Romans. That’s all.”

“As true as the current circumstances are now, Hosea prophesies none of that regarding Jesus,” Grace said.

“You don’t think this is prophecy?” I asked.

“Are you sure Hosea was talking about Jesus?” Christian asked.

“Who else would it be?” I asked.

“‘When Israel was a child’ is how the verse begins,” Christian said.

“But then Hosea prophesies about Jesus.”

“In the same sentence?” Grace said.

“Yep.”

“That doesn’t really follow,” Christian said. “Wouldn’t ‘he’ still be referring to Israel?”

“Maybe it’s one of the double things, where the prophecy means two things,” I said. “And wait, ‘he’ means one person. He can’t mean a group of people.”

“Old Testament authors often refer to Israel in the singular male or female form,” Christian said. “The prophets loved their pronouns.”

“Not this time,” I said. “This time ‘he’ means Jesus.”

“Okay, if ‘he’ means Jesus, what’s Jesus doing in the rest of the chapter?” Grace said.

“Um…bringing forth fruit and building altars and sacred stones,” I said.

“Jesus is building altars?” Christian asked. “That’s part of the prophecy?”

“Jesus could have built altars as a carpenter,” I said, “but I don’t get all the pronouns. They switch back and forth and stuff from ‘he’ to ‘they.’ Is it a copyist error?”

“Let me help you out a little, Cole. The word ‘he’ refers to the nation of Israel,” Grace said. “The word ‘they’ refers to the people of Israel who committed idolatry, according to Hosea.”

“That’s why you need to read these prophecies in context,” Christian said.

“But that ruins them,” I said.

“That’s what we’ve been saying,” Christian said. “They aren’t so prophetic when read in context. Context is important, even if context raises questions about these prophecies.”

“So, you’re saying it’s a big coincidence that Joseph and Mary fled to Egypt?” I asked.

“Matthew might have made that up,” Grace said.

“But Herod was a bad man,” I said.

“Matthew is the only gospel that claims that Herod slaughtered the children of Bethlehem. Mark refers to Jesus as a Galilean.”

“Luke says Jesus is born in Bethlehem, too,” I said.

“He does,” Grace said, “but that creates a problem when you compare the stories of Matthew and Luke.”

“How come?”

“Herod probably died in about 4 B.C.,” Grace said.

“Why does that matter?” I asked.

“Luke says that Joseph and Mary had to go to Bethlehem, the home of his ancestors, because of the census,” Christian said. “Censuses are generally taken for tax collection and other civic functions. Generally, you want to know where a person lives and works, not where their ancestors come from. If everybody moved back to the towns of their ancestors, that would cause chaos. Censuses are about creating order.”

“Maybe Caesar wasn’t so smart,” I said. “Maybe this was a dumb census where everybody had to travel to the homes of their ancestors for some reason.”

“Maybe,” Christian said, “but who was the governor of Syria at the time of the census?”

“Quirinius,” I said.

“Quirinius was a tutor to Caesar’s grandson before he became governor of Syria,” Christian said. “He didn’t become governor of Syria until 6 A.D. That’s a span of ten years between the events of Luke and the events of Matthew. One timeline has to be wrong.”

“Some translations make a note that it might have been before Quirinius became governor,” I said. “It could be that.”

“Maybe so,” Grace said. “That would square up the timelines, but why not simply mention who was ruling Syria at the time of Jesus’s birth. Why mention Quirinius at all?”

“I don’t get it,” I said.

“If I were talking about your birth,” Grace said, “I wouldn’t say you were born during Obama’s presidency because you weren’t. I wouldn’t mention Obama at all.”

“I was born under George W. Bush,” I said. “Neither of them was in the Bible.”

“Mentioning Obama when talking about your birth would confuse people,” Grace said. “I wouldn’t mention Obama at all. I would mention Bush. If Luke believed that Jesus was born during Herod’s reign, mentioning Quirinius would only confuse readers. The most logical conclusion I can make is that Matthew and Luke disagree about when Jesus was born.”

“Or you could say I was born before Obama was president,” I said.

“What would be clearer?” Christian asked.

“If you just said who the real president was when I was born, which would be Bush,” I said. “So…I guess Matthew and Luke thought something different about the dates Jesus was born because one of them didn’t hear God correctly.”

“Likely, Luke and Matthew disagree because they weren’t comparing notes,” Grace said.

“You’re ruining it all in a whole bunch of different ways,” I said.

“It’s only ruined if you take every word literally,” Grace said.

“Look, Luke wasn’t writing to complement Matthew’s text,” Christian said. “Matthew wasn’t writing to complement Luke’s text. They probably didn’t know each other existed, but they did know Mark. They likely fleshed out Mark in different ways for differing theological aims.”

“Why does that matter?”

“If they knew of each other,” Grace said, “they would be more harmonious. Interestingly, both Luke and Matthew change aspects of Mark’s story, likely because they didn’t think God inspired Mark. They were correcting the record for theological reasons, maybe. They both knew about Mark’s text, but Mark didn’t have a birth narrative. He focused on the ministry of Jesus, as well as his death and resurrection. By the time Matthew and Luke were writing, people probably wanted to know more about Jesus’ nativity. Matthew and Luke gave them what they wanted.”

“Maybe the nativity got cut off in Mark due to copyist errors,” I said.

“In ancient times, birth narratives were created for famous people,” Christian said. “Early believers, especially Greek believers, wanted a wondrous beginning for Jesus. Special births were common tropes in this sort of literature. The Caesars had special birth narratives. The demigods of Greek mythology did too. Even Moses had a special birth, just like Samson.”

“Matthew and Luke agree on the important stuff,” I said.

“They agree on the material in Mark that they liked,” Christian said. “They disagree when they add to Mark’s narrative. Both also worked hard to find prophecy in scripture, but in doing so, they worked a little too hard, and events fail to line up as well as they should.”

“Oh,” I said. “I guess I have two weeks from now to find better prophecies.”

“Good luck with that,” Christian said.

“It’s okay to believe these stories,” Grace said, “but we want you to understand why we question them.”

“For me,” Christian said, “the more I studied the Bible, the less I took it literally.”

“Same here,” Grace said.

“Oh,” I said. “I get the problem.”

“What do you get?” Grace asked.

“Too much Bible study,” I said. “Does that mean I should stop studying the Bible?”

“That, Cole, is entirely up to you,” Christian said.

In state legislatures across the country, Christian fundamentalists are passing laws meant to force the teaching of the Christian Bible in public schools. From the posting of textually inaccurate iterations of the Ten Commandments on the walls of classrooms to the incorporation of the “Trump Bible” across multiple pedagogical disciplines, these laws and mandates are sweeping the reddest parts of this nation.

The height of hypocrisy is banning books in the name of “protecting children” while mandating one particular book rife with numerous acts of sexual violence and scenes of graphic violence and genocide.

Book bans are dangerous. The Bible is worth reading and exists online and in public school libraries across the country, but proponents of mandating its formal teaching in public schools need to know what it actually says.

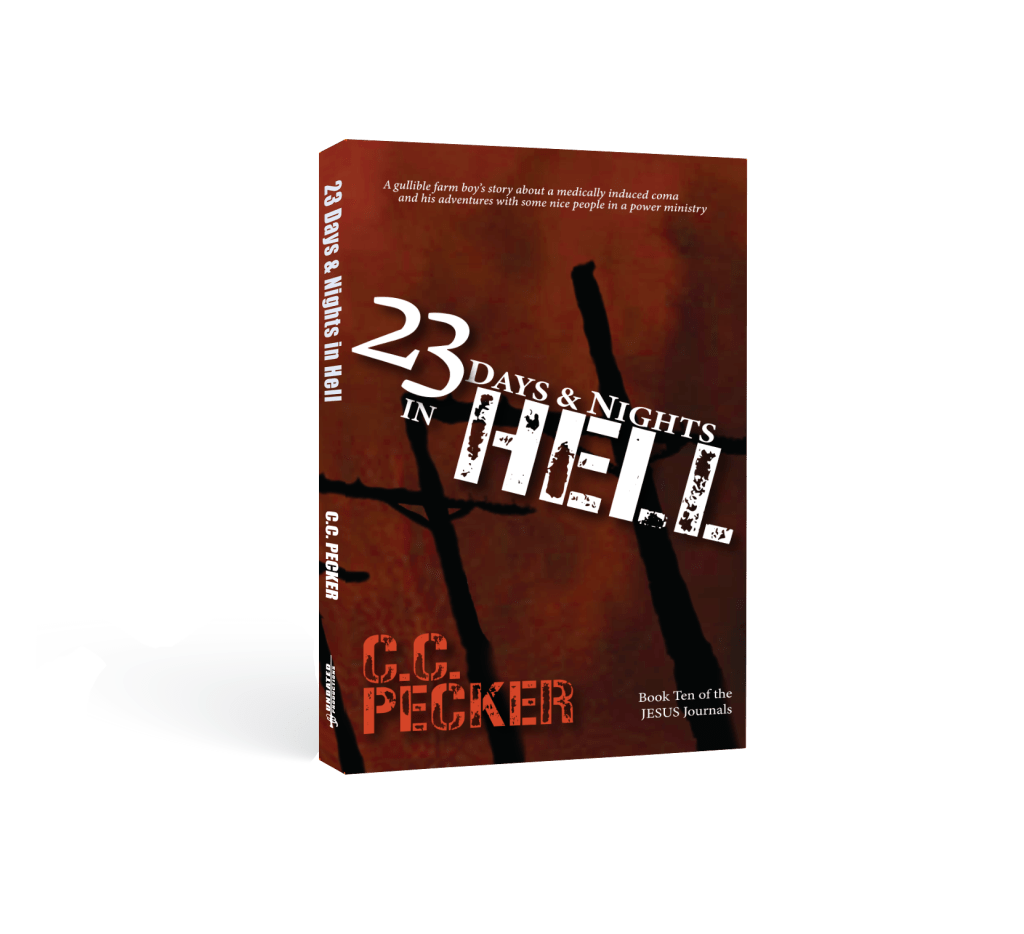

I’m making some videos for my books. I have the first one done. I hope you like it.

© Copyright UNBATED Productions 2026